Associate Professor of Media Studies

Anyone curious about the state of American democracy should simply tune into the GOP debate series, whose next episode airs Tuesday night on Fox Business Network.

If the first two debates are any indication, advertisers will be clamoring to buy up commercial spots, especially after the “buzz” generated last week: special conditions demanded by the candidates, Trump’s controversial – though dull – SNL appearance and the Ben Carson “bombshell” that he never applied to West Point (as he’d previously claimed). Yes, the debate has the makings of another ratings bonanza.

Televised presidential debates originated in the 1960s, during TV’s golden era. But back then, networks ran news divisions at a loss in exchange for being granted a licensed monopoly over public airways by the FCC. Candidates, in exchange for the publicity, answered hard questions posed by moderators.

Today, the rules of the debate game have shifted to reflect a new media reality, one in which broadcasters have a powerful financial interest in promoting debates centered on entertainment, rather than substantive discussions of policy issues.

In fact, today’s debates can be likened to World Wrestling Entertainment: there are heroes and villains, winners and losers, entrance themes and announcers, drama and intrigue (will Biden show?) – even an “undercard.”

Like it or not, the democratic process has been usurped by an endless, ratings-driven spectacle. And for networks – with the debates’ stripped-down production costs and high ratings – it’s like hitting the mother lode.

Record audiences yield record profits

Back in August, 24 million viewers watched the first GOP debate on Fox News. A month later, CNN drafted off this success, drawing 23.1 million viewers and selling commercials at US$200,000 apiece, roughly 40 times what they normally charge. And even though CNBC only drew 14 million viewers in the latest debate, it was the network’s most-watched show. Accordingly, they charged $250,000 per spot, a surge pricing rate that yielded record profits.

Tuesday night, 21st Century Fox and News Corp will list two of its properties – Fox Business Network (FBN) and the Wall Street Journal – as cohosts. It will be a big moment for the nascent network: their biggest show ever.

Even the undercard debate, which captured 1.6 million viewers for CNBC, will yield unprecedented audiences and profits for FBN, whose most-watched show drew a mere 152,000 viewers. No matter which network airs which show, the audiences this year dwarf anything seen in the 2012 GOP debates, which had a peak viewership of 7.6 million.

If, as Marshall McLuhan once speculated, the medium is the message, political rhetoric and modes of campaigning – at least for candidates whom TV talking heads call “electable” – have become indistinguishable from strategies used by TV networks to boost ratings.

In an age of slickly produced identity politics, the presidential debate series – part reality show, part melodrama – is a hit that bounces from network to network and features different personality types that appeal to different viewer demographics. Audiences get to “know” the contestants, and throwing their weight behind those they like and raging against those they hate, they’re deeply invested in their success or failure.

Though pundits and pollsters determine who wins or loses each debate, the media corporations who put on the shows – and who use the ongoing drama to pump up ratings for other shows – are the real winners.

Leveraging a hot commodity

And the candidates have noticed. Last week, while discussing the backlash CNBC received for asking hard questions, Rand Paul plainly expressed the new order:

We have a product that 20 million people want to watch. And so we should negotiate. People should bid for this. In fact, I think the networks ought to pay the Republican Party to air it.

Live debates, once commercial-free and sober, are now seen by politicians and networks as profitable entertainment products, viewed by audiences who have been conditioned to evaluate them as such. No matter how hard the media tries to comb over this bald reality beneath the ratings-driven political process, democracy in America has been hijacked by the entertainment industry.

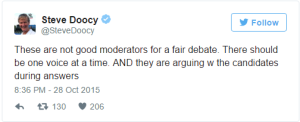

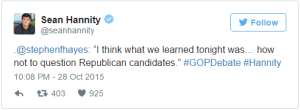

Viewed through this lens, the orchestrated pushback against CNBC after the last debate by candidates and pundits (who largely parroted 50-year-old complaints about “trust” and “liberal bias”) is nakedly cynical.

With Fox leading the charge, it’s clearly a strategy to drive up ratings for Tuesday’s show – and for Fox Business Network to grab some of CNBC’s market share.

Meanwhile, the GOP candidate demands last week for friendlier treatment from networks speak to a shift in power brought about by the profitability of the series, which the performers are now using as leverage.

In media we trust

As Donald Trump learned for 14 years on The Apprentice and The Celebrity Apprentice, big ratings demand sensationalism, polarizing personalities, catchphrases and conflict.

Yet this creates risk for the presidential candidates. Even though running for president gives you free access to media and fundraising machines, candidates spend enormous sums on ads across multiple media platforms to build their brands, and they need to protect them.

Moreover, the candidates’ commercials build awareness of the debate series, which then helps the networks sell more ads and drive ratings for all the shows the candidates appear on. With the success of the two players – candidate and media conglomerate – so tightly intertwined, it’s no surprise the GOP performers want more favorable conditions in return for the added value they bring to networks.

Ultimately, if there’s “trust” at work in the age of ratings-driven democracy, it isn’t between the media and citizens they purport to serve.

Rather, the producers and the performers – in this case, the presidential candidates – trust that everyone will follow the rules, generating entertainment for audiences and ratings for advertisers, while protecting the brands of the celebrities who are auditioning for a recurring role in the ongoing spectacle.

And that you can bank on.

Read this article on The Conversation (Nov. 10, 2015).