Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

In November 2000, newly elected New York Senator Hillary Clinton promised that when she took office in 2001, she would introduce a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College, the 18th-century, state-by-state, winner-take-all system for selecting the president.

Robert Speel

She never pursued her promise – a decision that must haunt her today. In this year’s election, she won at least 600,000 more votes than Donald Trump, but lost by a significant margin in the Electoral College.

In addition to 2016, there have been four other times in American history – 1824, 1876, 1888 and 2000 – when the candidate who won the Electoral College lost the national popular vote. Each time, a Democratic presidential candidate lost the election due to this system.

For that reason, views on the fairness of the Electoral College are often partisan. Not surprisingly, many Clinton supporters have called for its reform or abolition. But most recent polls indicate that supporters of both parties feel that this 18th-century system of choosing a president should be modified or abolished.

Nonetheless, others continue to make the case for preserving the Electoral College in its current form, usually using one of three arguments. In my course about American elections, we discuss these arguments – and how each has serious flaws.

The evolution of the Electoral College

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the delegates “distrusted the passions of the people” and particularly distrusted the ability of average voters to choose a president in a national election.

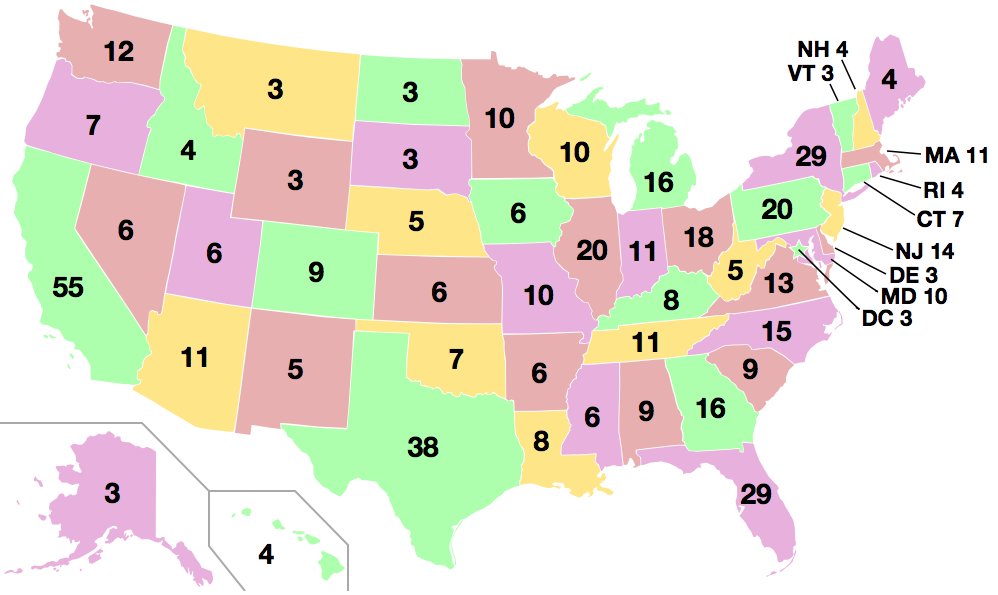

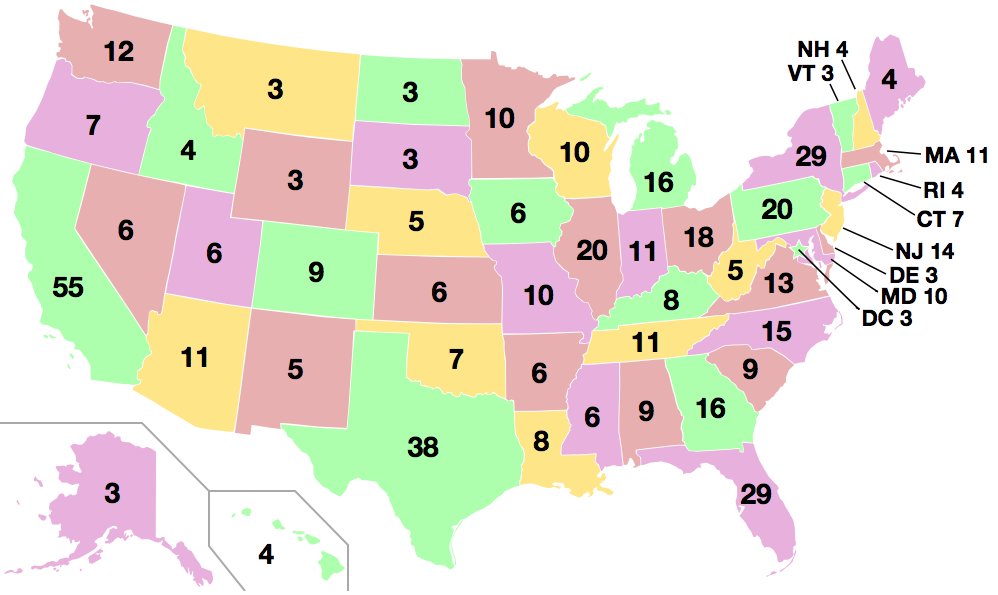

The result was the Electoral College, a system that gave each state a number of electors based on its number of members in Congress. On a date set by Congress, state legislatures would choose a set of electors who would later convene in their respective state capitals to cast votes for president. Because there were no political parties back then, it was assumed that electors would use their best judgment to choose a president.

With the rise of the two-party system, the modern Electoral College continued to evolve. By the 1820s, most states began to pass laws allowing voters, not state legislatures, to choose electors on a winner-take-all basis.

Today, in every state except Nebraska and Maine, whichever candidate wins the most votes in a state wins all the electors from that state, no matter what the margin of victory. Just look at the impact this system had on the 2016 race: Donald Trump won Pennsylvania and Florida by a combined margin of about 200,000 votes to earn 49 electoral votes. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, won Massachusetts by almost a million votes but earned only 11 electoral votes.

The winner-take-all electoral system explains why one candidate can get more votes nationwide while a different candidate wins in the Electoral College. (Some legal scholars have pointed out that the Electoral College was also created to protect southern slaveholder interests that are irrelevant today.)

Despite these issues, many continue to defend the system. Here’s why they’re wrong.

Myth #1: Electors filter the passions of the people

College students first learning about the Electoral College will often defend the system by citing its original purpose: to provide a check on the public in case they make a poor choice for president.

But electors no longer work as independent agents nor as agents of the state legislature. They’re chosen for their party loyalty by party conventions or party leaders.

In presidential elections between 1992 and 2012, over 99 percent of electors kept their pledges to a candidate, and there were only two “faithless electors.” One Gore elector from Washington, D.C. cast a blank ballot in 2000 to protest a lack of congressional representation for District of Columbia residents. And one Kerry elector in Minnesota in 2004 voted for vice presidential candidate John Edwards for both president and vice president – an apparent mistake, since none of Minnesota’s electors admitted to the action afterward.

There have been scattered faithless electors in past elections, but they’ve never influenced the outcome of a presidential election. Since winner-take-all laws began in the 1820s, electors have rarely acted independently or against the wishes of the party that chose them. A majority of states even have laws requiring the partisan electors to keep their pledges when voting.

Yes, some of this year’s Republican electors may not have been big supporters of Donald Trump’s candidacy. But despite the best efforts of some Clinton voters to get them to switch sides, there’s no evidence that some electors may consider voting for someone like Paul Ryan to prevent a Trump majority and throw the election into the U.S. House of Representatives.

Myth #2: Rural areas would get ignored

Since 2000, a popular argument for the electoral college made on conservative websites and talk radio is that without the Electoral College, candidates would spend all their time campaigning in big cities and would ignore low-population areas.

Other than this odd view of democracy, which advocates spending as much campaign time in areas where few people live as in areas where most Americans live, the argument is simply false. The Electoral College causes candidates to spend all their campaign time in cities in 10 or 12 states rather than in 30, 40 or 50 states.

Presidential candidates don’t campaign in rural areas no matter what system is used, simply because there are not a lot of votes to be gained in those areas.

Data from the 2016 campaign indicate that 53 percent of campaign events for Trump, Hillary Clinton, Mike Pence and Tim Kaine in the two months before the November election were in only four states: Florida, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Ohio. During that time, 87 percent of campaign visits by the four candidates were in 12 battleground states, and none of the four candidates ever went to 27 states, which includes almost all of rural America.

Even in the swing states where they do campaign, the candidates focus on urban areas where most voters live. In Pennsylvania, for example, 72 percent of Pennsylvania campaign visits by Clinton and Trump in the final two months of their campaigns were to the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh areas.

In Michigan, all eight campaign visits by Clinton and Trump in the final two months of their campaigns were to the Detroit and Grand Rapids areas, with neither candidate visiting the rural parts of the state.

The Electoral College does not create a national campaign inclusive of rural areas. In fact, it does just the opposite.

Myth #3: It creates a mandate to lead

Some have advocated continuation of the Electoral College because its winner-take-all nature at the state level causes the media and the public to see many close elections as landslides, thereby giving a stronger mandate to govern for the winning candidate.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan won 51 percent of the national popular vote but 91 percent of the electoral vote, giving the impression of a landslide victory and allowing him to convince Congress to approve parts of his agenda. In 1992 and 1996, Bill Clinton twice won comfortable majorities in the Electoral College while winning less than half of the national popular vote. (In both years, third party candidate Ross Perot had run.)

In 2016, Trump won by a large margin in the Electoral College, while winning fewer popular votes than Clinton nationwide. Nonetheless, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani announced that Trump’s Electoral College victory gives him a mandate to govern.

Perhaps for incoming presidents, this artificial perception of landslide support is a good thing. It helps them enact their agenda.

But it can also lead to backlash and resentment in the majority or near-majority of the population whose expressed preferences get ignored. Look no farther than the anti-Trump protests that have erupted across the country since Nov. 8.

A way out?

Some advocate that all 50 states adopt Maine and Nebraska’s system of dividing up electoral votes by congressional district. Yet such a system in larger states would likely lead to increased political conflict and even more claims of rigging due to the extreme gerrymandering often used to create the districts.

Abolishing the Electoral College completely would require a constitutional amendment, involving two-thirds approval from both houses of Congress and approval by 38 states – a process very unlikely to happen in today’s partisan environment.

One way to create a national popular vote election for president without amending the Constitution is a plan called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. Created by Stanford University computer science professor John Koza, the idea is to award each state’s electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote instead of the winner of the state popular vote. The proposal has received support in 10 states and the District of Columbia. But these states are all strongly Democratic, and there seems to be no support for the change yet among the majority of states controlled by Republicans.

Because Republicans won the two recent presidential elections where the electoral college winner differed from the national popular vote winner, many party supporters have defended the Electoral College as a way to preserve the role of rural (usually Republican) voters in presidential elections.

Rural states do get a slight boost from the two electoral votes awarded to states due to their two Senate seats. But as stated earlier, the Electoral College does not lead to rural areas getting more attention.

And there is no legitimate reason why a rural vote should count more than an urban vote in a 21st-century national election.

Robert Speel is an associate professor of political science at Penn State Erie. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.